Precious Penticton: Ironman Canada returns to its roots

One of the original Ironman qualifying races, Ironman Canada has a storied history in Penticton

Photo by:

courtesy Lynn Van Dove

Photo by:

courtesy Lynn Van Dove

Certain things, after time, simply ARE. They outgrow their origins, their owners, their masters. They take on a life of their own, a personality, a will. Lord of the Rings fans will recognize “The Precious” as one of those entities that can’t be categorized; to call it merely a “ring” is the ultimate blasphemy. The Precious is more compelling and more eternal than those lucky (or unlucky) enough to momentarily possess it.

The same can be said for Penticton.

For nearly 30 years, a small town in British Columbia has been home to “Ironman Canada,” and for five it was “Challenge Penticton.” Before that it was the Canadian International Ultra Triathlon, and the Canadian Ironperson Triathlon. But to the devotees who know it and love it, it is simply “Penticton.” It is the oldest long-course triathlon in North America, and its influence on triathlon, on North American multisport, and on the spectacle we now know as the “Ironman experience” cannot be underestimated.

Over the course of its nearly 40 years, Penticton has been mishandled, slandered, bankrupted, exploited, sold and stolen. Despite its passage through the hands of complex heroes, bandits, and grifters, it hasn’t lost its luster.

Related: Ironman Canada postponed to 2022

The athlete and the socialite

Ron Zalko had the vision for the very first 1983 race, and the race continued to evolve over the years. The event as we know it today is the child of two unlikely, but fated entrepreneurs. Both were inspired by Julie Moss (and also Jane Fonda), but came from totally different backgrounds.

Ron Zalko was 28 years old when he first learned what was happening in Hawaii. Formerly part of the Israeli navy, he had just started his self-named fitness studio in Vancouver in 1980, anticipating the aerobics craze. Jane Fonda famously taught at his studio and endorsed his signature workouts.

The Ironman World Championship triathlon had been running a couple of years in Waikiki when Zalko learned about it, and when it moved to the Big Island of Hawaii in 1981, Zalko was on the starting line. He returned to compete in 1982. He was hooked, though he calls it “probably the dumbest thing I’ve ever done.” At that same 1982 race, Julie Moss blew up triathlon by completing her legendary crawl across the finish line for second place. Julie Moss went viral (before viral was a thing), with ABC’s Wide World of Sports video being broadcast internationally.

Getting to the Hawaii race in the 80s was arduous for a Canadian. The international flight was expensive, and flight times were long. Bike shipping and transport weren’t yet routine and airlines had no idea what to do with a bicycle. Zalko recalls begging Air Canada to take his bike on the plane. He loved the challenge of Kona’s 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike and marathon run, but logistics of getting to Hawaii with all his gear was tiresome.

He thought, “why not do one of these in Canada?”

Related: Canada Triathlon Trivia – Ironman Canada edition

Lynn Van Dove (then Van Ert) was a Texan transplant in Penticton, having moved there with her partner. Socializing came easily to Van Dove; in Texas she was known for her massive, meticulously planned parties. But in small-town Canada, she was restless, needing a project. With some girlfriends, she opened a fitness studio in Penticton called BASE, inspired by the success of Jane Fonda, and became active in the local business community.

Van Dove, though not an athlete, had been captivated by the Julie Moss sensation, that famous video. She immediately recognized the drama and magnitude of that moment. It reminded her of the Oberammergau Passion Play in Germany, an hours-long reenactment performed only once every 10 years with a cast of 2,000 local villagers.

The town of Penticton was a tourism hot spot for the first half of the summer, when its legendary peach harvest was at its peak. But after the town’s July Peach Festival, the tourists packed up for the year. As part of the tourism board tasked with developing some kind of late-summer tourist draw, Van Dove immediately thought of Julie Moss.

She thought: “Why couldn’t a triathlon be done in Penticton?”

Van Dove gathered her girlfriends from the fitness studio – all wives and mothers – and produced a short-course triathlon, dubbed the Peach Classic in late July 1983 (that event continues today as one of the oldest continuously-running triathlons in the world). She recalls there were about 200 competitors. She and her friends planned the race in between their kids’ naps and meals. She recalls thinking, “this is just like planning a birthday party. We’ll have them swim, then ride their bikes, then run, and then we’ll feed them!” The Peach Classic was a promising success, and Penticton immediately formed a committee to manage future races.

Fated paths converge

Zalko thought of the Okanagan and Similkameen Valley regions of British Columbia for a potential long-course triathlon. The climate reminded him so much of Kona: Hot, hilly, windy. He first approached Kelowna, Penticton’s northerly neighbor, with the idea, but the town wanted a shorter event (which ended up being 1983’s Apple Classic Triathlon). Zalko didn’t want to produce a short course race. He wanted the big kahuna, a Kona-length event.

His reception was much warmer in Penticton, and he began filing paperwork to produce a race in August 1983. He’d never organized a triathlon.

Van Dove happened to be at the Penticton Chamber of Commerce when she spotted a brochure advertising Zalko’s race, which would be in just two weeks. She had just finished producing the Peach Classic a couple of weeks earlier, and immediately called the number on that brochure. She reached Zalko’s colleague Ralph Seigel, who offered her the position of assistant race director on the spot.

With just two weeks to finish planning, Van Dove once more collected her girlfriends from the BASE studio and said, “How would you like to produce a REAL triathlon?”

Two dozen stout-hearted men (and one woman)

Initially dubbed the Canadian Ironman Triathlon by Zalko, the Kona Ironman organizers issued a terse demand for a last-minute name change. “Ironman” was trademarked and could not be used. Van Dove simply crossed out the “man” and substituted “person,” and Ironman was satisfied with the change.

As Zalko and Van Dove rushed to finalize preparations, a pressing worry was finding enough athletes to compete. Zalko had to fund athletes to attend, and there was a real concern that no women would enter the race. The race paid the expenses of Dyanne Lynch, a Banff-based athlete, to attend. (She became, by default, the first female winner of the race that would later become Ironman Canada.) Twenty-six athletes eventually formed the start group at Lake Okanagan on August 20. Twenty-two of them finished the race (Lynch was 19th).

Zalko and Van Dove both recall the race went very smoothly. Despite a small group of participants, the town rallied around the event. Whole families came out to watch, especially after 10pm. Zalko recalls “I’d never seen anything like it, people coming out so late to cheer for the last people. I had tears in my eyes.”

Van Dove has similar recollections, including the incredible enthusiasm of volunteers, some of whom had been on the course for 18 hours. When some finish area volunteers were finally relieved, they didn’t go home – they stayed and cheered.

The race announcer for that year was Steve King, who later found fame as the “voice” of Ironman Canada. Van Dove recalls that King had his doubts prior to the race start: “I think he had changed his mind by the end of the swim! He grabbed the mic we had set up at the finish line and has never let it go.” Zalko remembers King climbing a tree to get a better look at finishers coming in for the finish.

Van Dove and Zalko both felt it, something deep in the gut. They’d created something exceptional, something that could be big… very big. And very precious. The battle to control it had already begun.

An icon is born

Van Dove continued to produce the race through 1991. A showman at heart, many features that not only became huge parts of the Penticton race, but became features at Ironman and other long-course events elsewhere, were added.

Van Dove wanted every athlete to feel like they were starring in their own movie. In her view, each moment of the race was choreographed to dramatic effect. For the first few years, every athlete got their own finisher tape. Much of these efforts were staged to attract Americans to the Canadian race.

The single-loop course

Penticton, to this day features a single-loop swim and bike courses, along with an out-and-back run.

Richter pass

Starting with 1984, the bike course to include iconic Richter pass. Van Dove initially fell for the entire Penticton area when first driving that pass, and she wanted athletes to summit it on the course. They still do today.

The soundtrack

A huge music fan, Van Dove knew that a rocking soundtrack would keep athlete, spectator, and volunteer energy up. Giant speakers were part of the Penticton setup from day one. A finish-line favourite for many years was “Heading for the Light” by the Traveling Wilburys. As athletes entered the water, Aaron Copeland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man” was played. The event’s original announcer, Steve King, is the “voice” of Ironman Canada, and is as much a part of the soundtrack as the music.

The pipers

The 1984 race was the first to feature the local Penticton Pipe Band – a troupe of bagpipers – leading athletes to the swim start. They still lead the race today.

The awards

Van Dove’s grandfather taught her how to draw perspective, and with an inherited drawing set, she sketched arguably the first “M Block”. A local wood sculptor created the awards based on her drawing.

The beer tent

The Kona race had a beer sponsor, and so did the Canadian race, which at first was sponsored by Molson, but later by Budweiser.

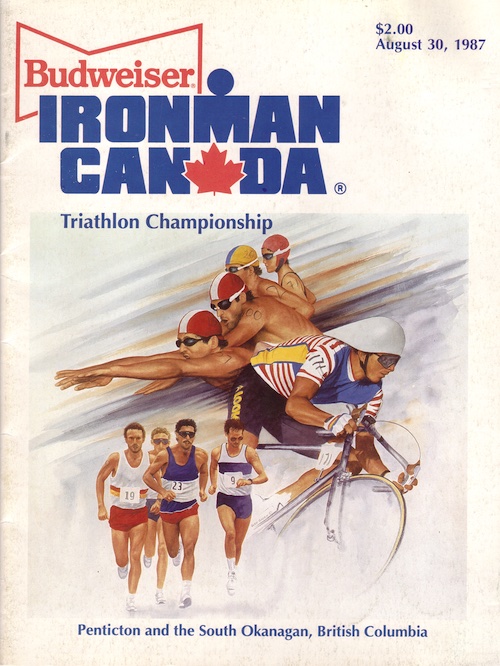

The art

The early years saw some amazing promotional posters, which Van Dove says were inspired by the artwork for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, combing athletics and graphic design.

A flawed history

Like most entities with staying power, the path to today wasn’t straight. The race didn’t start to generate a profit until the late 1990s. After Van Dove sold the race in 1991, subsequent owners had built registrations from less than 1,000 during the 80s and early 90s, up to a high of 3,000 in 2006. The race was selling out in hours. Athletes that had finished the race would camp out in the host hotel lobby to register first thing for next year’s event.

After becoming an officially sanctioned Ironman race in 1986, the Penticton Triathlon Race Society chose not to renew its Ironman contract in 2012 and instead contracted the event to Challenge, which produced the race from 2013 to 2017, along with a precipitous drop in registrations. The first Challenge year saw less than 300 entrants and found itself with a staggering $377,000 loss.

To much fanfare, Ironman announced it would again produce the race in 2020 after a two-year hiatus. That race, of course, was cancelled, as was the rescheduled Sept., 2021 race that year.

Despite changing ownership, local infighting, and a million petty squabbles, Penticton will be back again on Aug. 28, 2022. The pipers, we can report, are ready.

Christine Frietchen is a freelance journalist based in the U.S. and a regular contributor to Triathlon Magazine Canada. This story originally appeared in the Sept. issue of the magazine.