Given five years to live, Patrice Brisindi is making the most of his Ironman race time

Mental toughness personified

Photo by:

Marc-Andre Perron

Photo by:

Marc-Andre Perron

My media pass dangling from my neck, I was standing just a few metres from the finish line watching the pros run in at Ironman 70.3 Mont-Tremblant last June when Patrice Brisindi crossed the line in a time of 4:42:27, just 20 seconds behind Xterra star Melanie McQuaid.

“I survived,” Brisindi said, after catching his breath. “I think I finished third.… I had no legs for the run, so I am very surprised.”

For most of the race, Brisindi, 51, had been the man to beat in the 50-54 age group, but at the halfway mark of the run, a spring spent nursing an injured calf and dragging himself to train through a deep depression caught up with him. The calf had healed, and the depression had lifted, but he simply didn’t have the miles in his legs to repeat his 2021 Ironman performances, where he had topped the podium in Indiana, in a time of 9:20:39, then did it all over again in Cozumel seven weeks later with a personal best time of 8:45:55.

With that age-group win against a high-calibre field in Cozumel, Brisindi’s dream of a podium finish at Kona this fall suddenly seemed within reach — and it came just six months after his oncologist broke the news that his cancer had come back with a vengeance, and this time, with no hope of a cure.

“For sure, that came as a huge shock,” said Brisindi. A cycling buddy had accompanied him to the hospital to get the results of a PET scan, and afterwards, the two of them headed to the Gilles-Villeneuve racetrack in Montreal.

“I didn’t want to talk about it,” Brisindi said. “We biked around, talking about everything and nothing. Then, later in the week, I made the decision to try the one treatment they offered me. I was afraid of the side effects. I was afraid it would hurt my training.

But, at the same time, it was better than nothing. If I didn’t go for it, it was bye-bye.”

Brisindi and I had this conversation two days before the June 26 race, sitting on a sunny patio a stone’s throw from the gondola at Mont-Tremblant. He ate a burger and nursed a cold zero-alcohol Heineken as he talked. With his thick, salt-and-pepper beard and his slim, athletic build, he looked the picture of health.

Growing up on Montreal’s south shore, Brisindi had been a sporty kid: he swam competitively and played soccer and hockey. His dad ran marathons, but Patrice was more of a team-sport guy. By his late teens, he’d given up swimming and taken up cigarettes, and though he still played pick-up hockey, he lapsed into a sedentary lifestyle. It wasn’t until he was nearly 30, when his then-wife was pregnant with their daughter, Victoria, that he had a revelation.

“I was sitting in a restaurant, in a snowstorm. I ran out of cigarettes, so I had to go out into the storm to look for some. I walked and walked. I couldn’t find that magic convenience store out there anywhere!”

The stupidity of his addiction hit him as he returned to the restaurant empty-handed. He hasn’t smoked since.

Brisindi, who drives a bus for Montreal’s transit authority, started biking a few years later, encouraged by a couple of fellow bus drivers who were into cycling.

“I figured it would be good for my legs and strengthen my hockey performance,” he said. “One day, climbing Mont Royal, I crossed paths with a bunch of riders from the Saint-Lambert triathlon club. I started talking to one of the guys I knew, and he invited him to train with his club.”

Related: From Olympic contender to heart-transplant survivor

A couple of months later, in September 2006, Brisindi raced his first sprint at Esprit Montréal. He was hooked.

He did his first full Ironman at Lake Placid in 2010, at 39, finishing in under 10-and-a-half hours.

“I went into that race with no time in mind,” he said. “My goal was just to finish. But I did well, and then I thought, maybe I have an aptitude for long-distance racing.”

The year Brisindi turned 40 was calamitous. In April 2011, a 17-year-old student who had just gotten off Brisindi’s bus hopped onto his skateboard and skated right into the bus, just as it was turning. Pinned under the front wheel, the boy died. Brisindi, who had never had an accident in 20 years as a bus driver, was found not to be at fault. Still, he was devastated. He took stress leave, unable to face getting back behind the wheel. But he kept training — it was the only thing that helped. A few months later, he was back at Lake Placid. This time, he cut 20 minutes off his Ironman time. It earned him a Kona slot.

However, his first world championship race that October was no easy feat.

“An Ironman is hard, but Kona is something else entirely,” he said. “The heat, the wind, the high level of the athletes you are up against … I had a lot to learn.”

Brisindi had felt sick throughout the race, and when he returned to Canada, he still wasn’t feeling well. Blood tests showed his immune system was malfunctioning, which didn’t surprise him. His stress levels had been through the roof since the fatal accident. He hadn’t yet been able to return to work. Then, in January 2012, came the diagnosis: breast cancer, on both sides. Rare in men, but not unheard of. Brisindi underwent surgery, then months of chemotherapy and radiation treatments. It was a very dark time.

“There were times when I asked myself if I could keep going,” he said. “I treated it as if I was doing an Ironman. It was one day at a time.”

As much as he could, Brisindi kept training.

Related: Surviving COVID – Saskatoon triathlete goes from peak shape to barely breathing

“Even if it wasn’t easy, I’d go out to run, and all I could manage was three kilometres. I would walk 200 metres, run a little and I’d be out of breath. But just doing that much did me good. This sport is what helped me get through it all.”

With a few radiation treatments left by the fall of 2012, Brisindi raced the half-Ironman distance at Esprit Montreal, with the blessing of his radio-oncologist. By 2013, his cancer was in remission, and he was getting back into shape. Once again, he raced Lake Placid — his favourite course — determined to return to Kona. He missed the slot by a single place. When his hockey buddies heard this, they passed a hat and presented him with enough funds to get to Ironman Louisville just one month later. He got the slot, and two months after that, he was back at Kona, finishing in 9:50:47. Brisindi was back in the game.

So he was not really prepared for the news in May 2021, when he learned the cancer had returned. He was riddled with tumours, including telltale spots on each lung.

“It was a huge shock,” he said, “but maybe not as hard as the first time.”

Brisindi continues to work, loving once again his job as a bus driver. He works a split shift, swimming before the morning rush hour, then biking or running before he gets back behind the wheel in the afternoon. His cancer is incurable, but there is a drug treatment that gives him a 20 per cent chance of living five years. A year and a half since he started on that regimen, the drug is still working. Brisindi sings the praises of his oncology team at Charles-Lemoyne Hospital — and the triathlon community. His friends and supporters sing his praises, right back.

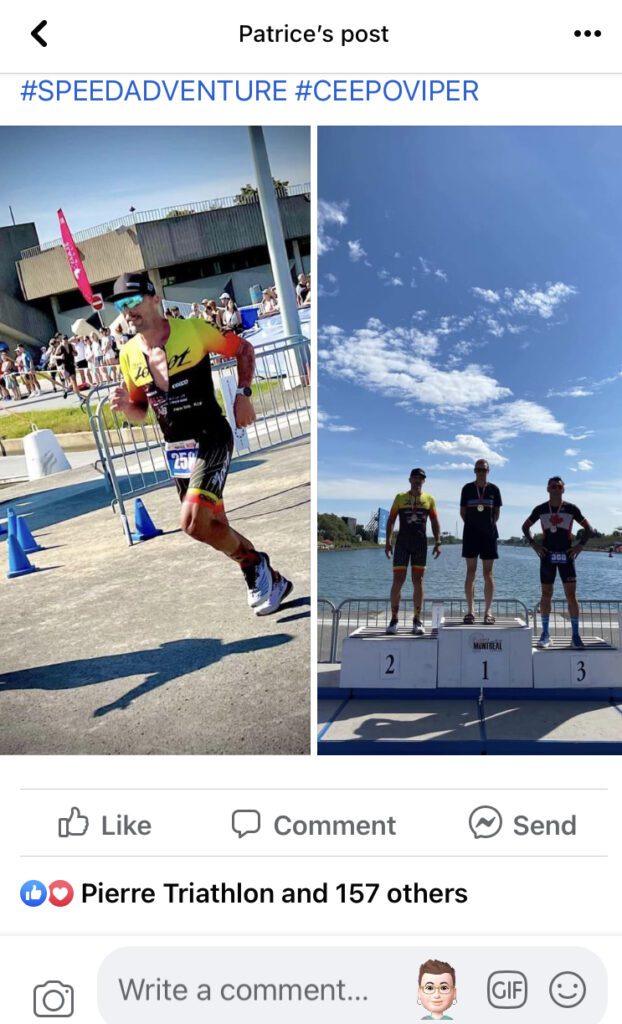

“I know a lot of people that, if you heard that news, you would probably sit on the couch and cry for the next five years,” said one of his sponsors, Marc-André Perron, the international sales and marketing director for Ceepo bikes, who outfitted him with a Ceepo Viper 2023 prototype to ride this past season. “But Patrice says, ‘I’m going to live the five best years of my life.’”

In late July, Brisindi called me to break the news that he has decided to give up his Kona slot this October. He has been tired, and he hasn’t had the stamina to put in the long hours needed to vie seriously for a podium spot — and that is still the dream. He has never been to the Ironman 70.3 World Championship, and so he was elated when Ironman offered him a spot at St. George, Utah this fall instead.

“I’m feeling good,” he said. “I’m feeling motivated again.”

“Can we say ‘mental toughness?’” Perron asks me, when I ask him how he’d describe Patrice Brisindi. “That is what he is.”

This story originally appeared in the Sept. 2022 issue of Triathlon Magazine Canada.