From Olympic hopeful to heart transplant survivor

After missing the 2008 Olympics because officials forgot to file his paperwork, Javier Cuevas's triathlon career would be cut short due to heart issues

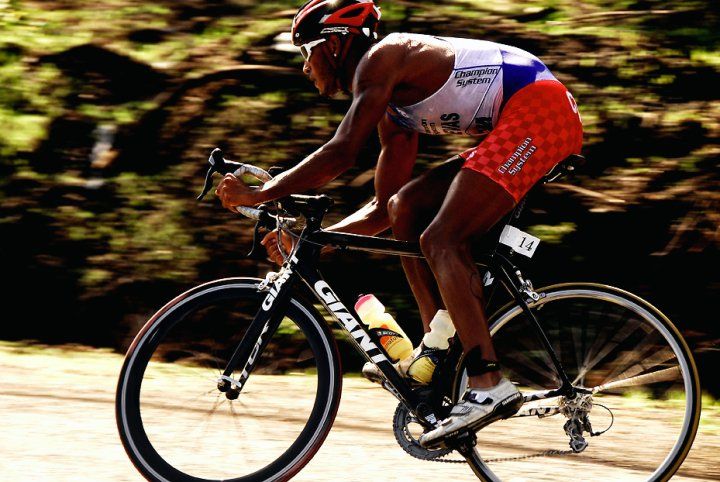

Photo by:

Courtesy FEDOTRI

Photo by:

Courtesy FEDOTRI

Looking back, Javier Cuevas can pinpoint the precise moment his heart became a ticking time bomb. It was June 20, 2009, the day before the ITU World Championship Series race in Washington, D.C.

“I was running in the park, and I just passed out,” he remembers. Cuevas, then 24, blew off the incident, putting it down to stress. “I raced the next day, but I did not race well at all. In the swim, the water quality was really bad and I hit a log, right in my face.”

Normally a front-pack swimmer in the international elite circuit, Cuevas came out of the water well off his usual pace, one second ahead of Simon Whitfield. He tried to make up time on the bike, but his race was over once he got lapped by a 21-year-old up-and-comer named Alistair Brownlee.

Cuevas, the seven-time national champion in his native Dominican Republic, had already proved he was no quitter. In the lead-up to the 2008 Olympics, he’d travelled the world on an ITU bursary to accumulate enough points to compete in Beijing, only to find out a month before the games that the Dominican Republic’s Olympic committee hadn’t filed his qualification papers. Devastated, Cuevas took some time off to salve his wounds, but soon set his sights on London 2012. His future on the international triathlon stage still looked bright.

He never made it to London.

Instead, Cuevas found himself watching the 2012 Olympics from his bed in the cardiology intensive care ward at the Montreal General Hospital. At 27, he had just suffered a massive heart attack. He’d been out riding with his training partner Phil Tremblay and a couple of other triathletes. Tremblay was biking home when he happened to spot Cuevas’s car pulled over on the side of the road, hazards blinking. Cuevas was slouched over, ashen-faced and not breathing.

“I called 911 and they told me to get him out of the car,” recalls Tremblay, 19 at the time. “I started to do CPR until the firemen showed up, pretty quick. They shocked him with the defib, like, seven times.”

“I am told I was out for 21 minutes,” says Cuevas. “No response. Pretty much dead.”

Eventually, the paramedics got a signal and rushed Cuevas to hospital by ambulance. He was put into an induced coma for 11 days to minimize brain damage from having gone so long without oxygen.

“I wake up, and it’s a sunny day. I’m looking out the window at the mountain, wondering what the hell happened. I say, ‘Was I in a car accident or something?’”

As Javier Cuevas describes the eight frightening years that followed, his hands tremble. It may be awhile before the signs of post-traumatic stress subside, and health challenges still lie ahead. But, with a new heart beating in his chest since Feb. 1, 2021, the one-time Olympic hopeful can finally breathe easy again, freed from what his cardiologist Dr. Caroline Michel likens to a daily game of Russian roulette: Was he going to have an arrhythmia today? Was the defibrillator implanted in his chest after that fateful heart attack going to work? Was his heart going to start again?

Cuevas was eventually diagnosed with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, or ARVD — a rare genetic disorder in which the heart muscle of the right ventricle is replaced by fibrous or fatty tissue.

“We’re all stressing the heart, every time we exercise,” Michel explains. “The heart always repairs itself. But in someone with ARVD, the heart doesn’t repair itself — in fact, it scars.”

The scars accumulate, eventually interfering with normal electrical signals, leading to irregular and potentially life-threatening heart rhythms.

“Javier was prototypical,” says Michel. “He was training 20, 25 hours a week. Every time he trained basically he would get more scar formation, and that scar formation causes arrhythmias, and arrhythmias can cause sudden death.”

An age-group triathlete herself with several 70.3 races under her belt, Michel is director of the heart failure clinic at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital. Her son Jeremy Obrand, then 16, trained with Tri-O-Lacs, the team Cuevas was helping to coach, and was one of the athletes out riding with Cuevas just before his heart attack. Michel had been devastated to find out her son’s coach had been suffering from unexplained fainting spells for years and brushing them off.

“She was pretty upset,” Cuevas says. “She said, ‘I’m a cardiologist! How could this be going on, and you weren’t telling me anything?’”

In retrospect, Cuevas now acknowledges, there were many signs that something had been seriously wrong. Less than a month after that first unexplained loss of consciousness in Washington in June 2009, it happened again — this time, on the bike leg at the ITU Pan American Cup and Central American championships in Puerto Rico.

“I remember going over a bridge, and I started to just fade away,” Cuevas says. “I come back, and I’m on the ground. I don’t know what the hell happened. I try to get on my bike, and my bike is broken. I am broken.”

Cuevas had cracked his collarbone. He didn’t dwell on why he’d passed out, blaming it on the stress of a poorly organized race that had been delayed for so long that the athletes started off in soupy water in the afternoon heat.

“Again, I blew it off,” he says. “I didn’t really want to deal with it. I kept trying to race; I was able to train. I was doing everything just normally.”

South African triathlon star Richard Murray reveals he has Atrial Fibrillation

Cuevas continued competing on the WTS circuit for another three years, until a race in Dallas in June 2012 that would turn out to be his last. Once again, he collapsed on the bike course, this time escaping with bloodied hands and a few bad scrapes. He told friends he must have nicked someone’s wheel. By then, the London Olympics were out of reach, so he returned to Montreal, where he was now living and working with his girlfriend, the Canadian Olympic triathlon team’s coach in Tokyo, Kyla Rollinson. One morning, soon after getting home, he passed out while swimming in the outdoor 50-metre pool at Parc Jean-Drapeau. Coming to at the bottom, he made it back to the surface and hauled himself along the lane rope to the pool’s edge. His swim buddy thought he’d been joking around.

“I was scared of the pool after that,” he says. “I didn’t want to tell Kyla.” Instead, he said he was taking some time off training. But he was shaken to the core.

“I’ve been swimming since I was three years old. This is all I know. This was the thing I liked to do, and now I could not do it because I was scared to drown.”

Then came the near-fatal heart attack and the struggle to accept that his triathlon career was over.

“To tell somebody at 28 who has been racing pro and elite, who is still on the national team for the Dominican Republic and still wants to go to the Olympics that you can’t do that anymore — well, that was just absolutely massive,” said Michel. But with ARVD, any activity that increases the heart rate poses a danger. After monitoring him on a treadmill, Michel ordered Cuevas to keep his heart rate under 100. It was not what her patient wanted to hear.

“I knew that I had a defib on, and there was to be no more racing,” he acknowledges. “I was just kind of like, OK, let’s get back to it.”

Cuevas felt fine for the first 18 months after his release from hospital, as long as he didn’t do anything too strenuous. He kept coaching from the sidelines, sometimes riding alongside his athletes on an electric scooter. But by 2014, the defibrillator was going off with alarming regularity. At first, it only happened while he was doing sports: he’d be out mountain-biking and he’d pass out, waking up on the side of the trail with chest pain. But over time, there were fewer and fewer activities he could safely do without provoking an episode.

“There were times when he was just barely functioning because he would have these cardiac arrests and get defibrillated,” explains Michel. “He’d get a bunch of shocks. It would happen in public places; it would happen when he was coaching kids at the pool.”

“I remember him calling me after a snowstorm. He was walking through the snow drifts because they hadn’t cleared the sidewalks to meet somebody for a coffee, and his defibrillator went off. It was absolutely terrible.”

The worst episode happened in the summer of 2016, while Cuevas was in the car with Rollinson on their way to Toronto. The weather was stormy, and at first Cuevas thought the sparks in front of his eyes were lightning strikes.

“I’d see a flash in my eyeballs, and I was like, ‘Kyla, are you seeing this?’” It was his defibrillator going off, again and again, while he was wide awake. Rollinson called Dr. Michel on her cell phone and rushed to the nearest ER.

“It was this middle-of-nowhere, small-town hospital, and they didn’t know what the hell was going on — this Black guy coming in, screaming his head off, jumping everywhere every time he got shocked.”

Michel advised doctors there what drugs to give Cuevas to stop the event, and they put him in an ambulance to Toronto. By the time her patient was stable and back in Montreal, it was clear tweaking medications was no longer going to keep him alive. In September 2016, Cuevas underwent a major operation, a nine-hour ablation led by Dr. Jean-Marc Raymond at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, to block the abnormal electrical signals causing the arrhythmia. For three months, he had his life back. He could ride his bike up Mount Royal. He no longer had to take beta-blockers. Then the episodes started again.

By now it was 2017, and Michel was regularly bringing up the topic of getting Cuevas on the transplant list. That had been the back-up plan in case the ablation surgery failed, but Cuevas, who’d just turned 33, still couldn’t wrap his head around it. He did agree to meet one heart transplant recipient, who told him how great it was to now be able to go for one-km walks.

It wasn’t what Cuevas was hoping to hear.

At a party over the 2017 holiday season, he learned about another Montreal athlete, a longtime competitive cyclist and occasional triathlete who’d been forced into inactivity by heart failure. Fifteen months earlier, in September 2016, Fabien Grignard had received a heart transplant at the McGill University Health Centre. Four weeks after his surgery, he celebrated by biking several laps of Montreal’s Circuit Gilles-Villeneuve at a brisk 25 km/h pace. By late fall, Grignard was back at his job at a bike shop and hiking in the Adirondack Mountains with his daughter Alexe on weekends.

Cuevas was incredulous. Still, another seven months would go by before he sent this message to the triathlete who’d volunteered to introduce him to Grignard.

“I would really like to have a chat with the friend you mentioned last time we spoke,” he texted. He said he was in hospital, recovering from a stroke.

“It means it’s time.”

Fabien Grignard had never had a moment’s hesitation about going on the transplant list. His life had spiralled downward quickly after the January evening in 2013 when he suddenly began coughing up phlegm. Grignard, who moved to Montreal from Belgium in 1989 in his early 20s, was a chef and a competitive Masters cyclist. He’d done a dozen triathlons, including a couple of half-distance races, and he’d signed up to do his first full-distance course at Mont-Tremblant to celebrate his 50th birthday in 2013.

“I was preparing for the Ironman, and sometimes I would be out running intervals and I just couldn’t do them,” Grignard recalls. “I thought I was overtraining.”

He’d booked an appointment with his doctor for February, but after googling his symptoms, he headed straight to the nearest ER. He was released a week later, a defibrillator implanted in his chest.

Grignard’s condition, familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, was genetic. The same disease had killed his father in Belgium, years earlier. Basically, his heart was no longer pumping efficiently, and it grew steadily weaker. He had to quit working as a chef, but by late 2015, even a sedentary job behind the cash register at a bike shop became too much for him.

“The doctor said, ‘Fabien, are you ready for the transplant? We can no longer wait. Your kidneys are failing. Your liver is failing. All your organs are starting to go.”

In May 2016, Grignard’s medical team installed an LVAD, or Left Ventricular Assist Device: a mechanical pump that did the work of his heart. A wire attached to the pump protruded from his lower abdomen and was connected to a computer and a battery, which he carried around in a backpack at all times.

“It was my resurrection!” recalls Grignard. “I could ride my bike again. I could even go camping, but I would have to take a spot with electricity and string the cable into my tent to plug in for the night. It was surreal.”

An artificial heart puts would-be heart recipients to the top of the transplant list, and Grignard got the call from the team at the McGill University Health Centre just four months later: they had a heart for him.

“I never had a moment’s hesitation. I never asked, ‘What’s going to happen?’ I was ready to die, but neither I nor my two adult kids ever dwelt on it. We just said, ‘See you later.’”

Grignard’s recovery was nothing short of remarkable. By the time he met Cuevas in August 2018, he was racing his bike again. That spring, he’d finished eighth overall in the 63 km Grand Prix cycliste de Sainte-Martine, just 25 seconds behind the winner.

“Look at this guy,” Cuevas remembers thinking, as they sat down together. “This guy is in shape!”

“Fabien reassured me. He was two years post-transplant already. He was doing races and training, and I’m like, this is a good outcome. That’s a case history I want to follow. So I told Caroline Michel, OK, put me on the list.”

Waiting for a new heart

Cuevas would have to wait more than two years to make it to the top of the transplant list. Michel says because he wasn’t on a mechanical heart nor bedridden in hospital on a drip, there were always patients whose cases were more critical. Then came COVID, and for most of 2020, no heart transplants took place at all.

“It was a pandemic, and the hospitals were jammed,” says Michel. “Javi knew, and he was completely on board — he just stayed home and didn’t move.”

The call came at the end of January 2021, with Quebec in a tight lockdown in the midst of the pandemic’s second wave. On Feb. 1, Cuevas underwent transplant surgery. There were complications that delayed his recovery, mostly due to an irritated trachea. But, three weeks later, Cuevas was home. One sunny day in May, Canada Post delivered a new pair of trail running shoes to his door.

“I started jogging a little bit. It was hard as hell. But the feeling afterwards was just amazing,” he says. “The euphoria you get from exercising, I am addicted to it! Those endorphins. As soon as I finished, I wanted to get out again, expecting better. And I knew I could train now without having to worry about ending up back in the hospital.”

A few weeks later, Cuevas was back on his bike, heading out on his first ride over Montreal’s new Samuel De Champlain Bridge with his cardiologist and her husband, vascular surgeon Dr. Danny Obrand.

Michel says the outing was wonderful, although it wasn’t easy to see how the long years of inactivity had taken their toll on the former pro. He was huffing and puffing up a two per cent grade.

“Going back, we rode on Danny’s wheel and we were pushing 50 watts. That first ride, that was as much as he could do,” she says.

Cuevas admits the pace of recovery has been tough on his ego, but slowly and surely, he is regaining strength.

In early July, he dropped by Cycles Gervais Rioux, the shop Fabien Grignard now manages. It was the first time the two heart-transplant recipients had met since Cuevas got his new heart. Grignard, who’s now 58, reported he’s racing Criteriums these days and doing long rides every weekend.

“We will go out for a 100-km ride on a Saturday morning, hitting 38 km/h when we’re pushing. Afterwards we will go out for a beer, and someone will say, ‘For an old guy, you are strong.’ I don’t even tell them.”

Cuevas isn’t up to day-long rides yet, but he has set himself a goal of completing Unbound, a 100-mile gravel bike event, in Kansas next summer.

The triathlete who saved his life, Phil Tremblay, looks forward to cycling with his old mentor soon.

“I lost a good training partner,” says Tremblay, “Seeing Javier on the sidelines, I just can’t imagine how hard it must have been for him. I’m just so happy he can now do the stuff he likes to do, because Javier likes to swim, bike and run.”

Montreal’s Loreen Pindera is a regular contributor to Triathlon Magazine Canada.

This story originally appeared in the September issue of Triathlon Magazine Canada.