The birth of Zwift … and why so many triathletes are addicted to it

Riding indoors is the answer to a bunch of problems, including bad weather, bad roads and bad drivers.

There are accepted and well-defined moments in every triathlete’s life where a choice is made to level-up.

The first, near universal moment is buying a “real” bike. Then, once the triathlon mania sets in, you want to get better, so you level up again. Maybe you’ll join a club or hire a coach. Next comes a power meter or a smart trainer. Then it’s downloading Zwift.

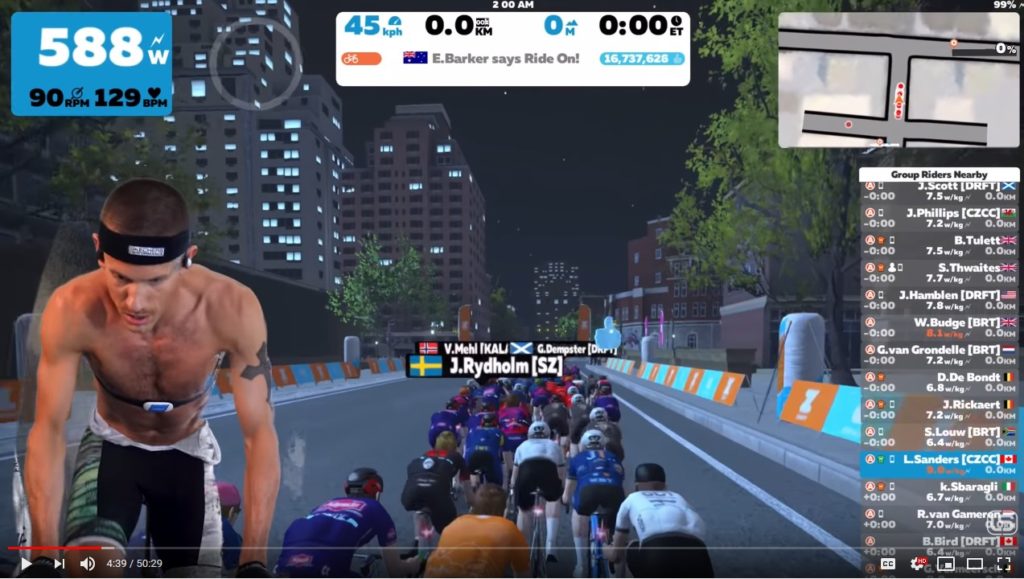

For the unindoctrinated few, Zwift is part training tool and part video game. It makes indoor bike training actually fun—and to some–even addictive; so addictive that some triathletes have given up riding outdoors altogether except on race days.

Riding indoors is the answer to a bunch of problems, including bad weather, bad roads and bad drivers. For young parents, it’s the solution to finding a babysitter or negotiating with a partner over who stays home. Yet, for all its upsides, riding indoors without the aid of distraction is mind-numbingly boring.

Boredom is the Mother of Invention

This was the reality faced in 2010 by California-based programmer Jon Mayfield: recently married, with a new home and a baby on the way, the new house was within eyesight of southern California’s Santa Ana River Trail, which every weekend attracted hundreds of local cyclists. One hybrid bike later and Mayfield was a newly minted cyclist. Flash forward six months and he’d upgraded to a cherry-red Specialized Roubaix, but with a newborn, getting out on the trail just wasn’t going to happen.

Meanwhile in another part of the world, tech entrepreneur Eric Min was thinking about a new challenge. He’d spent eight years as a VP at JP Morgan Chase in New York City, then had co-founded a London-based software company, where he’d spent another 15 years. But Min’s other passion was cycling.

Min had begun riding seriously at age 14 with Olympic aspirations. A successful amateur, he made it all the way to Olympic training camp. He loved racing, but almost equally, he loved the culture of cycling: the group rides, with guys jockeying for position and showing each other up, the trash talk, the bravado. He loved the social rides and friendships, the endless chats about gear and training.

And as a serious amateur, Min recognized the value in off-season indoor riding. But he hated it. Whether on rollers or a bike trainer, his indoor training was effective, but so boring. There was no one to talk to, no one to ride with, no one to compete against.

Around 2012, Min’s business life and personal passion converged. He found himself at a career crossroads, casting about for a

“Big Idea,” but it seemed that all the great new tech ideas were taken. His brother urged him to pursue combining what he knew best: technology and cycling.

New stuff on Zwift that we’re looking forward to this upcoming trainer season

Indoor Cycling was Spinning its Wheels

Both Min and Mayfield knew that indoor cycling had stagnated. The same basic bike trainers had been around for years. For triathletes and cyclists, one viable solution was CompuTrainer, which used proprietary hardware to control a trainer’s resistance on the rear tire. The company pioneered the electronic bike trainer, and for two decades was the only real player in the game.

Long before Garmin, the CompuTrainer setup allowed riders to collect and view cycling data, displayed on a screen during a ride. While revolutionary in the 90’s and 2000s, CompuTrainer had limitations. There were wires between the trainer and head unit, which complicated setup. You had to calibrate and warm up the system for a good 15-minutes before starting a ride or your numbers would be off. And the system was expensive. In today’s dollars, it would set you back more than $2,500, clearly out of reach for most.

And CompuTrainer was a closed system. It didn’t work with emerging wireless standards like WiFi, Bluetooth or ANT+. While the system included some rudimentary graphics, riders had just a plain road and a few blobby trees to look at, with a distant skyline or landscape. To facilitate group rides, bike shops would set up CompuTrainer studios, where cyclists could mount their bikes to a line of CompuTrainer systems side-by-side.

Enter the Disrupter

Zwift is the confluence of right time, right place, right people. A few years earlier and the technology would have been too expensive or too obscure. A few years later and other startups might have snatched market share. And if two people that had never met each other didn’t meet, then the know-how + investment + passion, with a big dose of nerdiness that resulted in Zwift would have never happened.

By 2013 Jon Mayfield had developed his own sophisticated solution for indoor training. Teaching himself to code, he gradually improved his “CRBike Coach” software. He was the only user.

Mayfield had created the graphics for video games for years, with credits on games such as Disney Princess: My Fairytale Adventure, Dreamworks Kartz, and Phineas and Ferb. His cycling program began as a little project over a Christmas vacation, where he wrote his first few lines of code in his home’s guest bedroom. He iterated on his side project for years, adding the ability to capture cycling data through a power meter and evolving the visuals. The very first virtual bike for the program was based on his own cherry-red Roubaix.

He began posting about his software on triathlon forums like Slowtwitch, looking for a partner or investor. He thought about creating a Kickstarter to try to find funding to make CRBike Coach into a real consumer product. Eric Min saw one of those forum posts and connected with Mayfield. By early 2014, they were co-founders of a yet-to-be-named project.

Gamer + Trainer

As Mayfield tinkered in his spare room, he drafted features that are at still for the core of Zwift: that at its heart, it’s a video game.

In an interview with Slowtwitch, Mayfield said, “I often get asked ‘Is Zwift a game or a training tool?’ It’s an odd question because training, to me, has always been a game. Whether I was trying to optimize my CdA in aerolab, trying to best my current FTP, or trying to move up a few percent on the local Strava segment, it’s always been gamified in my mind.”

His first version of his ‘game’ merely collected and graphed data from the bike on a screen. By 2011, he had developed a joystick that could be used to ‘steer’ in the game to collect coins while riding. From there, he figured out how to pause and return to the game, and he started using ANT+ wireless connectivity to communicate with the bike sensors.

Then came better graphics and some AI ‘riders’ to ride against. He made an Android app that could connect to the software over his WiFi network so a phone could be used as a display and input device.

By early 2014, he had added what he called “pain portals” that represented the start and end of an interval. Zwift users today will recognize those ‘portal’ entries; most now look like inflated archways, and riders still collect coins and points in the game.

After Min reached out, Mayfield hosted Min and co-founder Scott Barger in that same spare room to demonstrate his project. His heart was racing, finally getting to show his passion project to potential partners. He’d accidently left his heart-rate monitor on, so

Min and Barger were able to see just how nervous he was, with his HR graphed on the display screen while they spoke.

The World of Zwift

With a unified vision and the funding to match, the new company ramped up quickly, and by late 2014 was in beta testing. It officially launched to the public in October 2015, with a choice of two riding environments, the fantastical “Watopia” and the more realistic Richmond.

It’s a little disappointing that the company’s name wasn’t the result of a half-asleep, in-the-shower eureka, but rather, evolved out of sessions with a marketing agency. Even so, it’s apt, meant to suggest both motion and fun.

What started as a way to make cycling less boring has evolved into a powerhouse across cycling and triathlon. For around $15 per month and a compatible bike trainer, anyone ride one of Zwift’s nine virtual worlds, and users can make it as much of a game as they want. You can customize your avatar by switching out gear and clothing. The longer you use the program, the points you rack up, which allows you to “buy” upgrades within the game.

Just as with any video game, players reach levels (there are 50 levels currently), and receive badges and awards. But one of the most loved aspects of Zwift is the social integration. At any point, you’ll see a list of riders on the course with you, and they’re not AI…they’re actual people from around the world.

Do you Zwift? How you can join in on the online fitness explosion

Through the Zwift companion app, you can text other riders, or give them a “thumbs up.” The companion app also makes group rides possible. You can organize a meetup with friends or teammates, attend “celebrity” rides with pro cyclists and triathletes, and join pace groups. The Zwift platform hosts dozens of races every week, including the Zwift Racing League.

The exact number of subscribers around the world isn’t publicly available, but it’s believed that there are around 500,000 users worldwide.

It has been reported that subscribers nearly doubled during the pandemic. With no live events, and everyone stuck at home, Zwift was the perfect companion. The countries with the highest number of Zwift users included Spain and Italy, countries hard-hit by lockdowns.

According to Richard Melik, sports-marketing lead for Zwift, the pandemic accelerated some plans Zwift had already been discussing. Namely, a series of races featuring the world’s best triathletes. That became the Z PRO Race Series, which featured triathletes in their home pain caves competing for significant prize money.

Says Melik, “It was surreal to see athletes of the caliber of Gustav Iden, Kristian Blummenfelt, the Brownlee brothers, Flora Duffy, Georgia Taylor-Brown and Chelsea Sodaro all mixing it up on the roads of Watopia.”

What’s Next: Live Racing

Just as eSports evolved to live events where an audience watches elite gamers play World of Warcraft and other games in a auditoriums and arenas, Zwift has followed suit.

What started as a race series in triathletes living rooms has morphed into an entirely new type of event: a hybrid live/virtual triathlon.

As close as I’ll get to an MMA fight … Lionel Sanders enjoys spotlight at Arena Games Montreal

Dubbed the Super League Arena Games, this year’s series of three events featured a live audience watching pro triathletes compete in a hybrid environment. A pool swim was followed by live bike racing on trainers through Zwift’s virtual world, then a treadmill run, also through the fantasy environment of Zwift. It’s fast-paced, with athletes switching disciplines multiple times, all displayed for spectators on massive screens with pumping music and commentary.

Along with the PTO and Challenge/Clash, part of Zwift’s aim is to turn triathlon into a prime-time watchable sport with professional athletes and a legion of fans to follow them. The next events in the series, which began in Montreal, include events in Switzerland and Singapore. Spectators can watch in person or choose to stream the event, and the spectacle opens a new revenue stream for pros.

Says Melik: “We know that shorter formats of triathlon appeal to a wider broadcast audience. The Mixed Team Relays at the Olympics have been the gold standard in attracting a non-endemic audience to the sport and there are elements of Arena Games that mean it is well placed to do the same.”

For an age group triathlete using Zwift at home, watching the pros riding on Zwift is a thrill. Another level-up moment you won’t easily forget? Seeing Lionel Sanders or Lucy Charles-Barclay pass you while you’re riding one of the Zwift courses.

New to Zwift? The company offers a 7-day free trial to check it out. But we’ll warn you: it’s easy to find yourself addicted!