Inside the Age Group Mind: Training Transitions

– By Loreen Pindera

The guy who taught me how to use elastic bands to hook my bike shoes onto the frame and run barefoot out of T1 is a pro when it comes to quick transitions. He’s a pony-tailed speed demon, which is why Michel Brazeau was, not so long ago, Quebec’s top duathlete and Canadian champion in his age group.

But more than once – sprinting out of the transition zone at the head of the pack – Brazeau caught people laughing instead of cheering him on.

“I still had my helmet on,” Brazeau said. “I almost made a habit of it. At the Pentathlon des Neiges in Quebec City, I remember running half a loop before I realized my helmet was on my head.”

“I still had my helmet on,” Brazeau said. “I almost made a habit of it. At the Pentathlon des Neiges in Quebec City, I remember running half a loop before I realized my helmet was on my head.”

Oh, those pesky helmets. How often have you seen triathletes standing by their bikes in T1, wasting precious time on finicky strap adjustments?

Tony O’Keefe, a retired lieutenant-colonel who has raced every distance from sprint to Ultraman, recalls heading out on the bike course at Ironman Canada and catching up with a friend from Quebec who was cursing because, as cyclists passed him, they were smirking and asking him what direction he was heading in.

“His helmet was on backwards,” O’Keefe said. “Sometimes you just have to let dudes learn things the hard way.”

Every triathlete has a T1 or T2 story.

I was three kilometres into the marathon run in my first Ironman in 2009 when I realized I was still wearing my sturdiest bike shorts – like running with a diaper between my legs. I had to stop, strip down to my run shorts underneath and toss the bike shorts to the curb.

The lesson, for beginners and experienced triathletes alike, is minds turn to mush in transition. All you are thinking is “go, go, go.” But taking that extra second to take a deep breath, swig down some water (in that extra bottle that you remembered to place carefully next to your shoes) and run through a mental checklist that starts at the top of your head and ends at your toes is not time wasted.

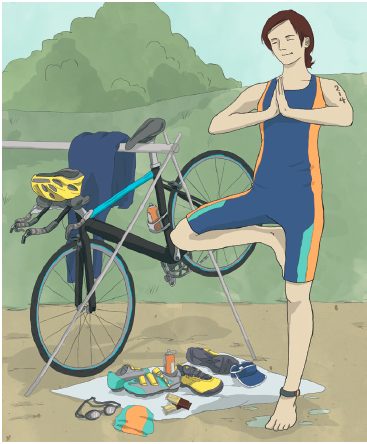

I did say “an extra second,” however. I have a friend who was so far ahead of her age group when she got off the bike, she decided to take five minutes to calm herself in a yoga pose – and missed qualifying for Kona by four minutes. True story.

Preparation and practice are key.

At the London ITU Grand Final in 2012, I watched my roommate France Saint-Denis lay out everything for T1 and T2 in order, on the floor of our dorm – just as she would the next morning. Then she jogged over to the transition zone in Hyde Park to walk through her transitions, exactly as she would the next day.

She does this for every race, starting from the precise spot where she will exit the water. “I will say, ‘I’m coming this way – and there’s a big tree here. There’s a fence there.’ I try to visualize it, because the course won’t look and feel the same the next morning when it’s full of bikes and people, when there’s music blaring and lots of action.”

Her tried-and-true method was born of experience. Arriving late at Oka for a race a few years ago, she deposited her gear in the transition area without taking the time to get her bearings, and she hit the beach just as her wave was entering the water. Saint-Denis found her bike with no problem in T1 and pedalled away, but running back in to hang it up she was disoriented and had to hunt around for the spot where running shoes were waiting.

Never again.

Practicing transitions means practicing them exactly as you’ll perform them.

“I’ve seen so many people trying to put their socks on wet, sandy feet,” Saint-Denis said, “and they discover in the middle of a race, it’s

not that easy.”

Same goes for no socks. Make sure your feet know your plans to slip them into your shoes. Blisters at eight kilometres in an Olympic distance race will slow you down more than the time it would have taken to slip on a pair of socks.

Preparation and practice – and you’re ready for anything. In 2011 it poured rain for two days before Mooseman 70.3. We arrived to set up our bikes and lay out our mats and shoes and discovered the transition zone was a swamp. Volunteers spent the night spreading hay to soak up the water, but the hay just made it swampier and slippery. No matter, the race was on. Running from the frigid lake into T1, we stripped off our wetsuits standing ankle-deep in sludge, slung our bikes over one shoulder, grabbed our soggy shoes and helmets and headed to drier land. Transition times were as slow as molasses. The race was a blast just the same.

Loreen Pindera is a triathlete and an editor and broadcaster at CBC News in Montreal.