Triathletes making a difference – putting races on during a pandemic

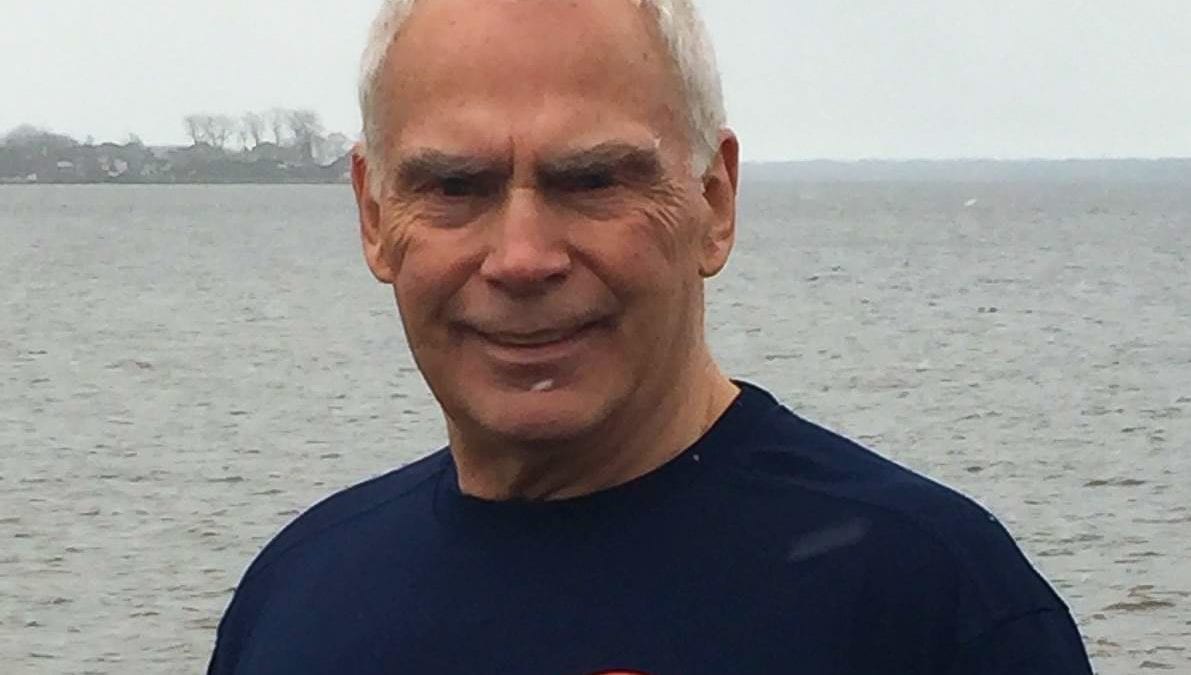

Danny McCann and René Pomerleau managed to hold things together to put on races during last year's pandemic

When Danny McCann, the veteran organizer of one of Canada’s oldest triathlon festivals, Montreal Esprit, sat down with his inner circle to figure out how to hold the 36th annual event in the midst of a global pandemic, he thought they had left nothing to chance — right down to ordering hundreds of masks and face shields for volunteers, and measuring precisely how many square metres each cyclist would have to themselves on the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve track for the bike leg of their race.

McCann was convinced that Esprit could be a physically distanced event that would meet the most stringent public health requirements and, above all, keep participants safe from COVID. He planned to hold a full slate of races with no cap on the number of competitors. It could go off without a hitch, he surmised, providing every athlete understood the rules, arrived at the event site on Montreal’s Notre-Dame island at their assigned time and left immediately after their race.

Then, on Sept. 10, two days before the Esprit weekend, word came down from public health officials in Quebec City that the number of participants on site would be strictly limited to 250 — and that until those 250 competitors had left the island, no one else would be allowed on site.

McCann and his team were flabbergasted.

“We’d had two different site visits from public health professionals that very week,” said McCann, “including the fire department — the boots on the ground for everybody. And they all told us they were very pleased with our whole plan.”

With less than 36 hours to go before the first wave was set to hit the water, organizers had no choice but to turn the entire event into a sprint-only race, with four waves of 250 triathletes over two days and four hours between the morning and afternoon waves, to ensure all athletes had time to clear off the island before the next group arrived.

Many race organizers would have thrown in the towel. But not the indefatigable McCann.

“We were not going to go through all that we had to plan for the event only to cancel,” he said. “We had talked about it, and we said, ‘Hey, no point in arguing. We will do whatever they say we have to do.’”

Save the date

Traditionally the festival that caps Quebec’s hectic triathlon season, Esprit was only the second major event of the year in the 2020 racing season that wasn’t. A week earlier, the Trimemphré club in Magog, in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, held its 25th anniversary event, which had originally been scheduled for mid-July but was postponed after the provincial government forbade all organized sporting events.

“It was way harder to get permission to hold a triathlon than it actually was to stage the event itself,” said Trimemphré’s race director, René Pomerleau.

Trimemphré wasn’t able to secure a firm date for its postponed race in the scenic tourist town until the popular local wine festival scheduled for the September long weekend was cancelled.

“We grabbed the date,” said Pomerleau.

The provincial triathlon federation, Triathlon Québec, helped the race organizers draft 15 pages of protocols outlining all the precautions they would take to protect participants from COVID and precisely how they would stage the race. Things were so uncertain that Pomerleau waited until just three weeks before the proposed weekend to open registration for the race. At last, they got permission to hold a one-day, sprint-only event, with shorter distances for youngsters.

“It went off without a hitch,” said Pomerleau. “The athletes followed all the rules 100 percent.”

“In fact, it went so well under the COVID rules, that we think we will just keep many of those rules for future triathlons.”

For instance, each athlete was assigned an individual start time, right down to the second, and they were asked not to show up to get their race packet more than an hour in advance. Each had an assigned place in the transition zone, just like in an Ironman race, and the precise scheduling meant every athlete had a bike rack to themselves. The purpose was to keep athletes physically distanced, but staggering the swim start times so that one athlete hit the water every 15 seconds also proved to be safe and efficient.

McCann, too, believes after trying out staggered starts in 2020, Esprit will never go back to mass swim starts.

“To me, that’s the worst part of the triathlon,” he said. “The staggered start really worked well. I really, really liked it.”

Esprit also ran like clockwork, although McCann said “we eliminated all the fun.”

“We eliminated the food tent, the expo, the awards ceremony, the spectators. All that was gone. It took years to get that atmosphere, and we had to do without it. But the athletes raced.”

“Both Esprit and Magog deserve kudos, holding events under the circumstances they did,” said Jean Piolé, the events coordinator for Triathlon Québec. “It took so much energy, so much time. Many people would have been totally demoralized.”

Pomerleau and McCann and their teams have provided a blueprint for how triathlons can be raced next season — a season which both organizers agree is almost certain to proceed under pandemic restrictions.

“What I’d tell other triathlon organizers is, don’t give up,” said Pomerleau. “Have faith in your athletes. We sent every participant a whole package of guidelines to follow, and they followed those rules 100 percent.”

McCann said triathlon organizers now have the winter to make contact with public health officials and help them to understand triathlon racing — and that they can count on the compliance of the participants.

“The athletes are committed,” McCann echoes. “They all wore their masks. They want to stay healthy. They came because they trained for this.”