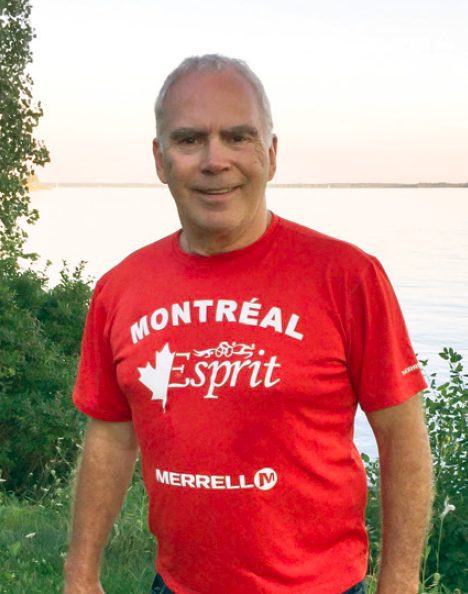

Legacy leader: Meet Esprit’s Danny McCann

Danny McCann, race director of Montreal Esprit Triathlon, shows no signs of slowing down.

— By Loreen Pindera

As soon as I heard the news this spring that the City of Montreal would be closing the Gilles Villeneuve racetrack to cyclists for the whole summer, I fired off an email to Danny McCann.

“What about Esprit?” I asked.

“No problem,” came his immediate reply, short and sweet. “We got Esprit.”

The racetrack, 4.6 kilometres of seamless asphalt that winds its way around Île Notre-Dame, a short ride from downtown Montreal in the city’s Jean Drapeau Park, is a training ground for cyclists and triathletes from the instant the snow melts. That is, except for the annual weekend in June when it’s dedicated to the Formula One Grand Prix, for which it was built.

Last spring, to the fury and discontent of cycling enthusiasts, the city announced it would be moving outdoor rock concerts to the track while a nearby outdoor venue undergoes renovations.

McCann, however, leaves nothing to chance. The organizer and race director of the Esprit triathlon, now in its 33rd year, booked the Sept. 9 and 10 race weekend for 2017 the day the 2016 race was over last fall.

McCann, however, leaves nothing to chance. The organizer and race director of the Esprit triathlon, now in its 33rd year, booked the Sept. 9 and 10 race weekend for 2017 the day the 2016 race was over last fall.

“The circuit will be cleaned off well before our race,” he promised. McCann is a businessman – his family-run company supplies tools to the heavy construction industry, he has a stake in a multi-rink sports complex in Montreal’s West Island and, ever since his own pro hockey days in Switzerland 45 years ago, he’s had a gig on the side sending Canadian hockey players to Europe.

The Esprit triathlon is his labour of love. It may be unpaid work, but he runs it just like any of his other enterprises.

“You’re always working at it, always thinking about how to make it better,” he says, whether that be cleaning Ikea out of $6 blankets for the medical tent after spotting them on sale or figuring out how to build a better racking system for thousands of bikes on race weekend.

Triathlon was a brand new sport when McCann organized the first Esprit race in Montreal in the early 1980s. The best-known long-distance triathlons in North America at that time were the Ironman races in Hawaii and Penticton, B.C. His hockey-playing days behind him, McCann ran 10K a day to keep in shape. He dreamed of going to Kona, but he couldn’t swim four lengths of the pool.

“I was like a windmill out there, thrashing around in the water,” he recalls. He joined a masters swim club and learned to float and keep his body pointed in one direction. He signed up for Kona in 1987 and, although kayakers still had to paddle out to him to steer him back on course, he managed a 1:20 swim and fulfilled his ambition.

“Once I did what I had taken up the sport to do, I was very happy with that,” McCann recalls. He competed in a few more triathlons at the standard and sprint distance, but he transferred his abundant energy and organizational acumen into building the sport in Quebec.

In Esprit’s early days, organizing the event was basically a one-man show, with the help of McCann’s wife Beverley and no more volunteers than the McCanns could fit around a dinner table.

Today, he has a core group of 30 volunteers and a stable of 600 more for race weekend, most of them athletes from sports as diverse as the McGill women’s basketball team to a dragon boat club to a Nordic ski team. The teams use the event as an annual fundraiser: A sizeable chunk of Esprit’s $200,000 budget goes to honorariums for their athletes’ volunteer efforts.

“The teams can take that money and spend it on travel to a tournament or uniforms or whatever they want,” he said. “The volunteers are there to help out their own group. And we know because of that, they’re going to show up, even if it’s raining.”

Some years, the rain has been torrential: in 2011, there were whitecaps on the sheltered Olympic rowing basin where the swim takes place. But regardless of the weather, the pace is fast.

“We have the fastest race in the world,” McCann boasts. Thank the Formula One racetrack for that. When Esprit hosted the International Triathlon Union World Championships in 1999, the ITU insisted on setting a counter-clockwise course. That meant the prevailing wind was at the riders’ backs, and some of them clocked in at 65 km/h on the straightaways. Needless to say, the bike course has been counterclockwise ever since.

And with no vehicles on the bike course, the biggest danger is vertigo from going around and around – 21 times to make 90 kilometres – and losing track of your laps. The race kit used to include a row of little coloured stickers to affix to your handlebars. You were supposed to remove one after each lap. Nowadays, Sportstats supplies a digital display board that’s not foolproof, but a lot tidier for McCann, who was stuck cleaning up what looked like wedding confetti pasted to the track after every race.

The 1999 ITU World Championships was a pinnacle for Esprit, but McCann had to take six months off work to pull it off. And after 23 years offering the full distance, Esprit dropped the 140.6-mile race in 2015, because there are now three major Ironman events within driving distance of Montreal. McCann has taken Esprit in other directions instead, content to build on the event’s reputation as the ideal race for an age-grouper just starting out in the sport.

“We get 30 per cent first-timers every year,” said McCann. To help them get over their jitters, Esprit offers a free seminar before the race on what to expect, talking newbies through issues like how to enter and exit the water, getting through transitions and what to expect on the course.

“This is the ideal half to start with,” said McCann. “I had one guy tell me, ‘I want to get my wife to do Mont-Tremblant, but I’m trying to convince her to start with your race, so she can see that she can do the distance.’”

This year, in addition to the half distance, the duathlon, sprint and Olympic events, there will be a try-a-tri race, U13 and U15 events for kids and a Grand Prix event for elite athletes with $5,000 in prize money.

McCann was inducted into Triathlon Canada’s Hall of Fame in 2009 for his contribution to the sport. At 67, he could choose to rest on his laurels. He can’t run anymore, since falling off a ladder right after the Esprit some years ago and breaking his leg badly. But other than that, he’s not slowing down.

“I have no plans to quit,” he says. “I think I could still run this when I’m 80 years old.” There’s little reason to doubt him.