Is heart rate training still relevant?

Have new training metrics eclipsed the old means of gathering information, such as heart rate, thereby rendering their use a time-wasting exercise?

— by Kerry Hale

Recently, I found myself discussing with the owner of my local bike shop the merits of smart trainers and virtual riding software. He espoused the benefits of both with great enthusiasm, and talked about how the landscape of sport – certainly cycling – has forever changed due to advancements in the efficacy and convenience of virtual training and racing. Our conversation centred on training metrics, notably wattage and heart rate.

“Heart rate training is kind of dead,” he said, catching me off guard. “It’s almost a redundant metric nowadays. Times have really changed.” Granted, he was alluding to cycling, but his words got me thinking: is heart rate training, in cycling and triathlon, really dead after all?

Related: What is Heart Rate Variability?

For eons, heart rate training has been the most common training methodology. Typically, heart rate readings have operated in conjunction with a stopwatch, cycle computer or poolside clock to act as a gauge of exercise intensity. Heart rate monitors are relatively cheap, accessible and simple to use. They provide a relatively accurate snapshot of training or racing intensity.

But technology has infiltrated the sports of cycling, running and triathlon as athletes look for more and more detailed metrics. Have these relatively new metrics eclipsed the old means of gathering information, such as heart rate, thereby rendering their use a time-wasting exercise?

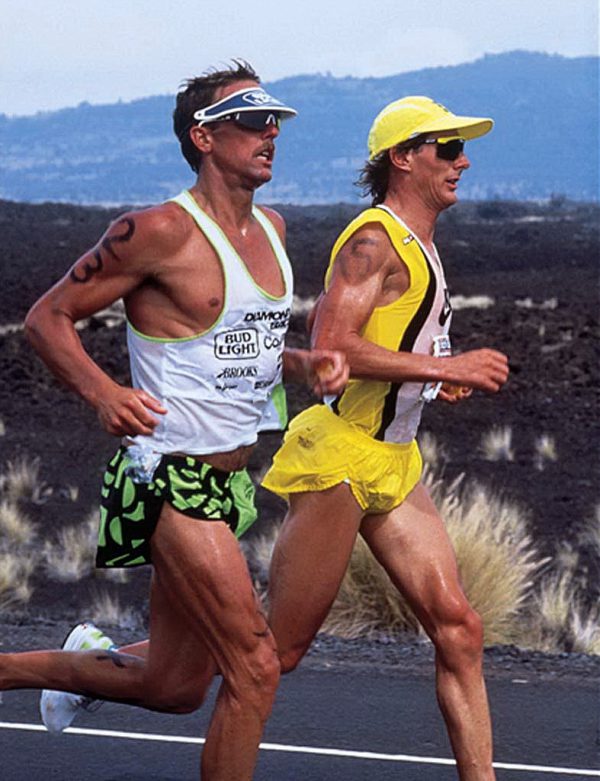

Ironman champions Mark Allen and Dave Scott are both virtual triathlon encyclopedias. Their feats have become folklore. To say that their records have stood the test of time is an understatement. Their results, at a time when technology in our sport was in its infancy, were staggering. While neither man competes any longer, both are at the forefront of coaching and mentoring many of the world’s best triathletes. Their understanding of “old school” training approaches is undeniable. Add this to a vast knowledge of current cutting- edge training practices, which include all the modern metrics, and you have a duo who can rightfully speak on the subject of whether or not heart rate training really is “kind of dead.”

Related: Coach Paul Duncan: How to determine your threshold heart rate

“I still think heart rate is the gold standard for setting an athlete’s training zones,” Allen says. “Whether your goal is to win a race or just live a long healthy life, using a heart rate monitor is the single most valuable tool you can have in your training equipment arsenal.” Based on his swim background, Allen lived by the “no pain, no gain” training philosophy that was commonplace at the time: “My coach would give us workouts that were designed to push us to our limit every single day. I would go home dead, sleep as much as I could, then come back the next day for another round of punishing interval sets. It was all I knew.”

When he entered the sport of triathlon in the early 1980s, Allen’s approach was to go as hard as he could at some point in every single workout to keep pace with other big names in the sport, most notably Dave Scott. By his own admission, he had some good races the first year or two, but also suffered from minor injuries and was always feeling one run away from being too burned out to want to continue with his training. Then, says Allen, “came the heart rate monitor.”

He worked with Phil Maffetone, who felt that he was doing too much anaerobic training, too much speed work, too many high end/high heart rate sessions. He was given a heart rate monitor and was told his “magic number” was 155 beats per minute. For the next four months, he did exclusively aerobic training, keeping his heart rate at or below his 155 beats per minute (bpm) maximum aerobic heart rate. In under a year, he went from running 8:15 min/mile to 5:20 min/mile at the prescribed 155 bpm. More comfortable and less taxing than the anaerobic style, he had become “an aerobic machine.”

After finding one’s maximum aerobic heart rate (the highest heart rate you can train at and still burn mostly fat for fuel), Allen suggests doing cardio training at or below this heart rate. Once speed plateaus, return briefly to high-end interval anaerobic training for one or two days a week. “This is what I did to keep improving for nearly 15 years as a triathlete,” Allen says.

Other measures can be used along with heart rate, Allen suggests, including pace and power metrics. “But if you are just measuring pace alone and you see increases over a period of time, you will never know if the improvement is because the athlete is more fit or because they are going harder,” he says. The same concept applies to using power in cycling. “Without the heart rate to gauge your power numbers against, you would never know if an athlete has become fitter or is just going harder on that day.”

Related: Heart rate zones defined

“Heart rate training doesn’t have the impressive sound of training with power or doing physically demanding testing to get a result that will set your zones,” Allen adds. “But I’ve tried working with every option out there and still, after over 35 years in endurance sports, I am solidly convinced it’s the best method for setting people’s training zones.”

The only other man to have won the Ironman world championship six times is Dave Scott, who agrees with Allen on the importance of monitoring heart rate during training. “There is still a lot of relevance for triathletes in heart training,” says Scott. “This information, definitely, has a place in the training toolbox. The heart rate monitor, really, is every person’s tool. “The universal tool you can use across the board is the heart rate monitor because it’s so adaptable. The power meter, on the other hand, while a fabulous tool, is expensive and definitely has limitations, cost being one of them.”

Scott notes that, due to the simplicity of using heart rate, even if an athlete doesn’t know how to use it properly, it can still be very beneficial. He reiterates that by cross-referencing heart rate data with speed and time, an athlete has a powerful, cost-effective tool.

It’s in hot and humid conditions that Scott really subscribes to heart rate usage. “In hot areas, you need sufficient recovery time to allow the heart rate to come back down, typically to 30 to 40 beats below lactate threshold, and this is where monitoring bpm can be very advantageous.” For Scott, a heart rate monitor is a great way to “governor the system.”

Scott also points out that for short, intense training segments of under three minutes, heart rate lag is an issue, so he recommends not using heart rate to gauge such short efforts – speed should dictate the intensity. When increasing the interval length to beyond 15 minutes, which taps a mix of the aerobic and anaerobic systems, Scott advises using various tools to monitor the intensity, including heart rate.

Related: Power vs. heart rate: Which is the better tool for training?

It is worth noting that neither Allen or Scott overly critiqued the use of other modern-day metrics to determine training intensities. Both readily acknowledge they deserve a place in endurance sports. Both agreed, however, that using these metrics, including power, lactate threshold and other measures, lose their effectiveness without cross-referencing these numbers with a fundamental baseline – that baseline being heart rate readings.

The words “gold standard” and “universal tool” ring loud from two legends of our sport. It seems my local bike shop owner, in his haste for techno-progress, may well be disregarding the most valuable – and the original – metric of workout intensity.