Remembering Dave Mirra

If anyone else can make any sense of the news that rocked both the cycling and triathlon world last week, I hope they can enlighten me sometime soon. I met Dave Mirra a few times over the three years he’d become a triathlete, even spending a few hours with him at the Cervelo offices in Toronto last March for an extensive interview, and every time came away with the feeling that he had to be one of the nicest guys on the planet. A man who seemed so at peace with himself, his family … his life.

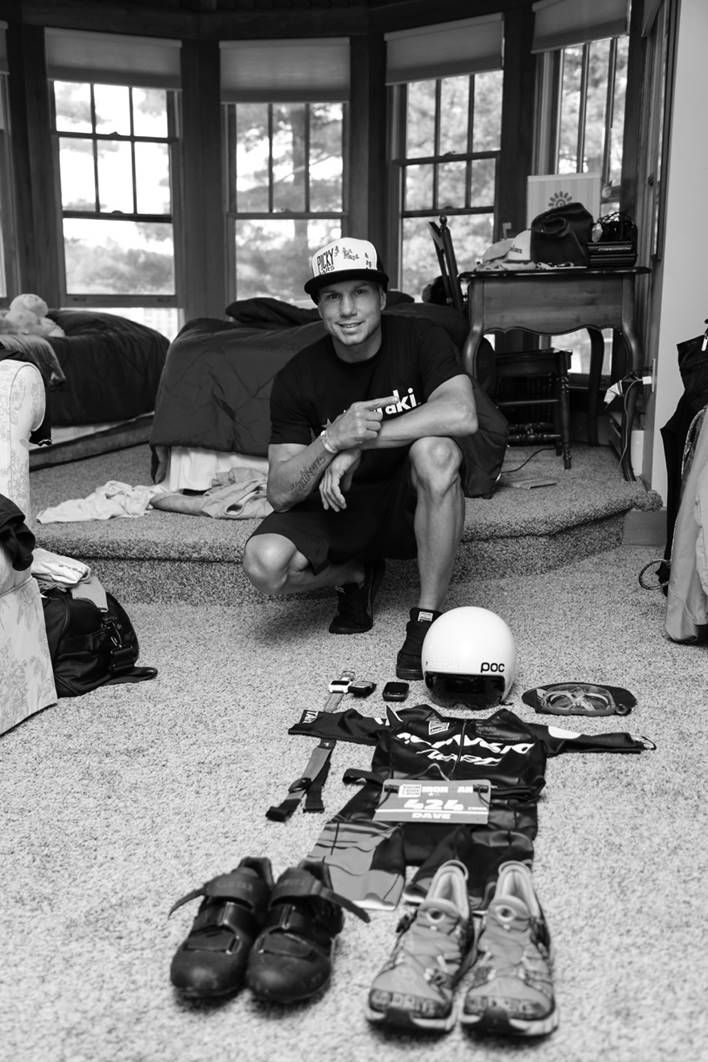

Which is why the news that Mirra had allegedly taken his own life last Thursday night came as a huge shock. I’d been sitting on the interview I did with Mirra for almost a year. I had hoped to use it when I got to report that he’d qualified for the Ironman World Championship in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii last year, but his 11-hour performance in Lake Placid last summer wasn’t enough to qualify him for the big show. While he was enough of a “celebrity” that he could have got into Kona as a media athlete, Mirra had turned down that opportunity. He wanted to get to Kona as a qualifier, just as he’d done in 2014 when he qualified for the Ironman 70.3 World Championship in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec.

sitting on the interview I did with Mirra for almost a year. I had hoped to use it when I got to report that he’d qualified for the Ironman World Championship in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii last year, but his 11-hour performance in Lake Placid last summer wasn’t enough to qualify him for the big show. While he was enough of a “celebrity” that he could have got into Kona as a media athlete, Mirra had turned down that opportunity. He wanted to get to Kona as a qualifier, just as he’d done in 2014 when he qualified for the Ironman 70.3 World Championship in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec.

“I wouldn’t have wanted to be there if I hadn’t qualified,” he said to me last March. “It was awesome to be part of the group.”

Being part of our “group” meant a lot to Mirra. From day one he’d tried to be a face in the crowd, taking inspiration from his friend Eric Hinman, who he’d watched compete at Ironman Lake Placid. He was amazed at Hinman’s dedication. “I saw his training, his intense dedication, and decided I needed something to fill a void,” Mirra said.

Mirra bought himself a bike in December, 2012. He brought it home and immediately started to fiddle with the fit, jumping on his rollers and trainer and dialing in his position, just as he’d done for over 30 years on his BMX bikes. As much as he tried, he wasn’t ever just a “face in the crowd.” He actually led the way for a while in his first race, coming off the bike in second despite getting lost. Whether he liked it or not all of us in the media would track him down for interviews whenever he appeared at a race.

He wasn’t quite as passionate about triathlon as he’d been about his BMX career, but he wasn’t far off. BMX had been his ticket out of Chittenango, a small town in upstate New York. Even before he was 10 years old he used to ride 20 miles on his BMX bike, with all his equipment no less, just to be able to get to a ramp to train on. In grade six he used to sit in his social sciences class, reading BMX magazines.

“So, does that bike have a bell on it?” the teacher said to him. “You’re never going to make it in life.”

ESPN tracked that teacher down during Mirra’s heyday as one of the greatest X-Games athletes in history and he admitted that he never figured Mirra would amount to anything. Mirra laughed as he recounted the story.

It’s not like it was easy, though. When he turned pro Mirra would win a grand total of $200 for a win. He’d work at state fairs, doing BMX displays, and earn $100 a day. He and the other riders would get $15 a day for food. It wasn’t exactly living the high life.

It’s not like it was easy, though. When he turned pro Mirra would win a grand total of $200 for a win. He’d work at state fairs, doing BMX displays, and earn $100 a day. He and the other riders would get $15 a day for food. It wasn’t exactly living the high life.

He could care less. He loved to ride his bike. If the ramp opened at noon, he’d be there at 7 getting ready. He had two VCRs and a camera so he could watch videos of his BMX heroes, and also of his own tricks, honing in his technique. All that led to an X-Games career that included 24 medals, 14 of them gold. Mirra inspired so many with his amazing feats. He became one of America’s most famous athletes. And never once did that seem to go to his head.

Mirra recognized the intensity that helped him achieve all that, and it scared him. In 2011, when he signed up for a boxing match, he spent six weeks living with his friend Laird Hamilton (and Hamilton’s wife Gabrielle Reese) in Los Angeles. He left his wife, Lauren, and two kids Mackenzie and Madison back at their home in North Carolina as he trained six days a week in a boxing gym on Sunset Boulevard.

“This is what scares me about the full distance,” Mirra said. “I just change as a person. It’s like a first relationship in high school, where not a second goes by in the day when you’re not thinking about the person. That’s how I am – with the boxing and with Placid. I keep living it in my head.”

He’d say that, then, minutes later he’d be talking about his kids and incredibly supportive wife.

“I have no pressure,” he said of his triathlon racing career. “Doing this is a great example for my kids.”

As I listened to that interview again today, I was struck once again at just how nice a guy Dave Mirra was. You can hear the vibration of his phone throughout our chat – he was ignoring texts from a rally team who were trying to convince him to get back in car and do some racing. (Amongst his many talents he’d also raced rally cars for Subaru.) I kept trying to tell him my interview wasn’t that important – he would have none of it.

Mirra’s death shocked those of us who had the privilege of meeting him. For a “face in the crowd” he affected a lot of us.

Our thoughts are with his family and friends through this terrible time.